Thomas Egan lives in Kilcolgan, Ferbane in Co. Offaly, in a house bought by his father who came from Endrim. Thomas explains that he knew his uncles in Endrim, and that his paternal grandparents were small farmers. In earlier days, people would cut enough turf to set aside for winter, and every house would have turbary rights, he says. As a young lad, he would earn some money saving turf for others. He recalls turf being brought to Dublin for storage there for the use of the poor. The local agents and contractors who would draw lorry loads of turf around the country are also recalled. During the Emergency there was no coal coming in to the country, so turf and timber was much in demand. He speaks about the importance of cold winters for the generation of business. The briquette factory at Cloghan is now closed, he explains, adding that he recalls contractors such as Popes coming up from Cork to collect the turf. Before the onset of mechanisation, the Board would begin preparing the bog for the summer work, but with good drainage the bog is now firm and easily worked by machines. Thomas explains that local knowledge of wet areas of the bog was very important. In Upper Boora there were hostels at the local Bord na Móna site, with accommodation and food provided. He remarks that some men would prefer to work for themselves on their own bog, particularly if there were a few sons in the household. This was particularly the case during Thomas’s childhood when there was less paid employment. The families were dependent on the turf especially since there was no social welfare or other assistance.

Thomas was reared in Leamanaghan. He attended primary school about a mile away from his home, and secondary school in Ferbane. He recalls his first teacher, Mrs Hickey, and the principal, Mrs Daly, in the two-room national school. The school day ran from 9am to 3pm, and every pupil who was in a position to do so would provide the turf for the two fireplaces in the school. When the fuel ran out, the pupils would be sent out to find some timber. The natural surroundings are discussed and Thomas recalls the bleakness of the cold, windy and frosty weather. The hard work and the routine of life is remembered. At night there were rambling houses to visit and card games to be played, and the neighbourliness and friendship of the people are recalled. He reflects on the fact that a lack of education was a barrier to emigration, particularly if money was short or the family did not know somebody who lived abroad. Other barriers were shyness and a lack of confidence, he says. Thomas was never married but does not bemoan this fact. He was reared with his two sisters and a younger brother with his mother and uncles while his father lived elsewhere. When he began work with Bord na Móna his pay packet helped out in the household, and as a result his siblings received a better education. His mother’s great efforts on behalf of her family are remembered. Thomas began work in 1954 on the bog at Leamanaghan, and later he worked at Turraun. His first job involved working with a group of about 20 men making the railbeds through the bog, and he describes this work. That bog was in production from the 1960s to about 2000, and he recalls the contractors’ lorries queuing on the road to collect the turf. The bog now produces milled peat for Shannonbridge power station. He explains that an average of 12 feet in depth was cut from the bog. He recalls the discovery of a bishop’s crozier in Leamanaghan bog and describes how this wonderful discovery was made. This artefact is now in the National Museum in Dublin.

At Turraun Thomas worked on machinery. When he began, his first job was to drive a screw-levelling machine, and he describes its operation. Later he worked on a bagger with some others. Each working day was divided into three shifts, he explains. He recalls the 100-ton machine with a 54 metre conveyor which he operated, powered by electric motors and built in Ireland. His first machine was diesel powered and was made in Germany. Before his time, the machines were powered by the Board’s own power house. Thomas recalls the German engineer, Harry Starken, who married a local woman and settled down in the area. Starken had his own bog in Edenderry from which he sold turf. Thomas explains that he went on to develop another bog for the production of moss peat at Bellair. He drove a machine there for about two years. Later he was appointed area supervisor with between 30 to 100 men on his team. He remembers developing the virgin bog and describes the wildlife disturbed during the process, and he discusses the change from boglands to pastoral lands once the peat has been dug out. The issue of the ban on turf-cutting is considered, as is the local feeling and upset about this ban. A comparison is made between the thousands of acres of bogland being cut by Bord na Móna and the small area cut by locals. Thomas remarks that most people are not working on the land nowadays in any case, so this is not as big an issue as it might have been in earlier years. In his opinion, slavery is removed from the work of today in general because of mechanisation.

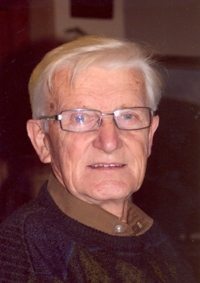

Thomas Egan (b. 1935)

Thomas Egan (b. 1935)

€10.00 – €20.00

Additional information

| Type: | MP3 |

|---|---|

| Audio series: | The Offaly Collection: memories of early industrial peat harvesting at Turraun |

| Bitrate: | 128 kbps |

| Download time limit: | 48 hours |

| File size(s): | 44.7 MB |

| Number of files: | 1 |

| Product ID: | CDOF09-03 |

| Subject: | Changing times on the bog |

| Recorded by: | Maurice O’Keeffe – Irish Life and Lore |